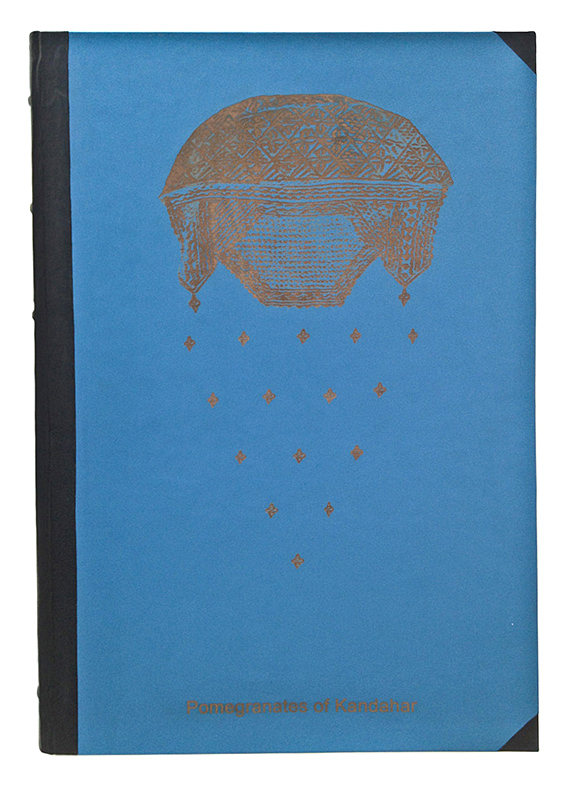

This book, comprised of woodcuts and poetry, comes from a world that has been kept obscure and described only in fragments.

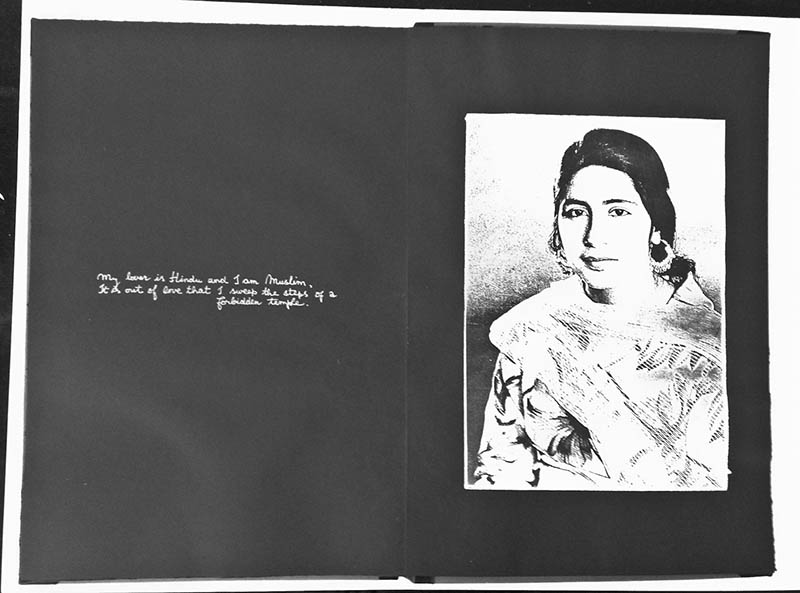

The photographs, which the woodcuts are based on, were taken in the Pakistani city of Peshawar, the capital of the North-West Frontier Province and the gate to Afghanistan. The Province is home to the Pashtuns, who also form the majority of people in Afghanistan. The Pashtuns have always crossed the borders of both countries freely.

In the 1960s and 70s, photography was in full bloom in Peshawar. Society enjoyed, in comparison to today, a liberal period. Photographs of young girls, women, and couples who showed affection were commonly seen. I have a large number of such photographs in my archive, primarily acquired in 2012 from two photo studios in Peshawar’s city center, Capri Studio and Jamilistan.

Many of Peshawar’s photo studios have discarded their negatives in recent years; they were either of no use and a burden to keep, or destroyed out of fear of attacks by religious extremists. A large number of photo studios are located on the old Cinema Road. As the name implies, several cinemas were located on this road, but only one remains open today. All but one of the cinemas were attacked and shut down by religious extremists who see the effigy of man as sacrilegious. Shaken by the attacks on Cinema road, many photo studio owners now fear for their livelihood.

On one of my first journeys to Kabul, I came across Sayd Majrouh’s book Le Suicide et le Chant in its English translation by Marjolijn De Jager, titled, Songs of Love and War: Afghan Women’s Poetry. Sayd Majrouh is one of Afghanistan’s most famed 20th century poets. In 1989, while in exile in Peshawar, he was assassinated by extremists. The Landays he collected by Pashtun women are from the same time period as the images in my archive. A Landay has twenty-two syllables – nine in the first line and thirteen in the second. They are composed anonymously and shared collectively, passed down and adapted by each generation. These short poems and their unbounded wittiness undermine Pashtun social codes in which women are prohibited to speak openly. Landays are only spoken by women.

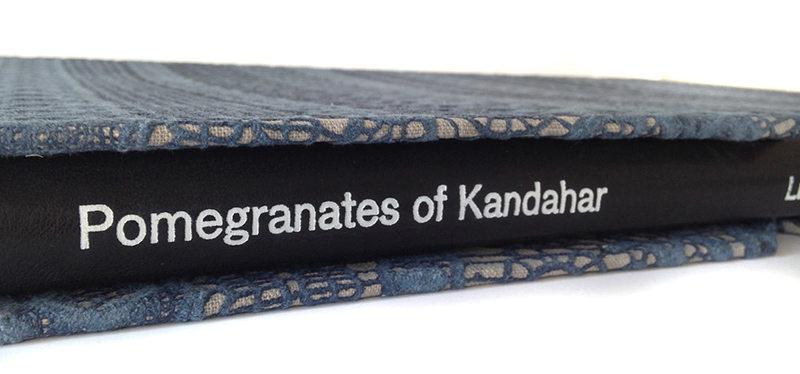

The book merges Marjolijn De Jager’s handwritten translations of Landays collected by Sayd Majrouh with the woodcuts I created from the photographic negatives of Pashtun women in my archive

The book comes in an edition two as well as four sets of prints.

More information on visual culture in Peshawar can be found in the book I c0-authored with Sean Foley called Photo Peshawar.